- The salt is a random string that is added to the password before the hash to achieve unique hashes per user.

- Linux It stores hash, salt and algorithm in /etc/shadow, strengthening security against dictionary attacks and rainbow tables.

- Good practices require long, random, and unique salts, along with robust hash algorithms and databases well protected.

- Password salting should be integrated into broader security policies that include strong passwords, MFA, and password managers.

If you work with GNU/Linux systems or are simply concerned about the security of your accounts, you've probably heard of salt in the password hashIt's one of those concepts that's mentioned a lot, but often only half understood: it sounds technical, but in reality it makes the difference between a system that's easy to break and one that's much more resistant to attacks.

In short, salt is a key element to making password hashes unpredictableIt works by adding random data before applying the hash algorithm so that, even if two users have the same password, the result stored in the database will be different. From there, the specific implementation in Linux, its relationship with /etc/shadow, tools like mkpasswd, and modern security best practices are a whole world in themselves, which we will explore in detail.

What exactly is the salt in a password hash?

In cryptography, a salt (salt) is a random string of characters which is appended to a user's password before applying a hash function. The goal is for the resulting hash to be unique even if the plaintext password is the same for multiple users.

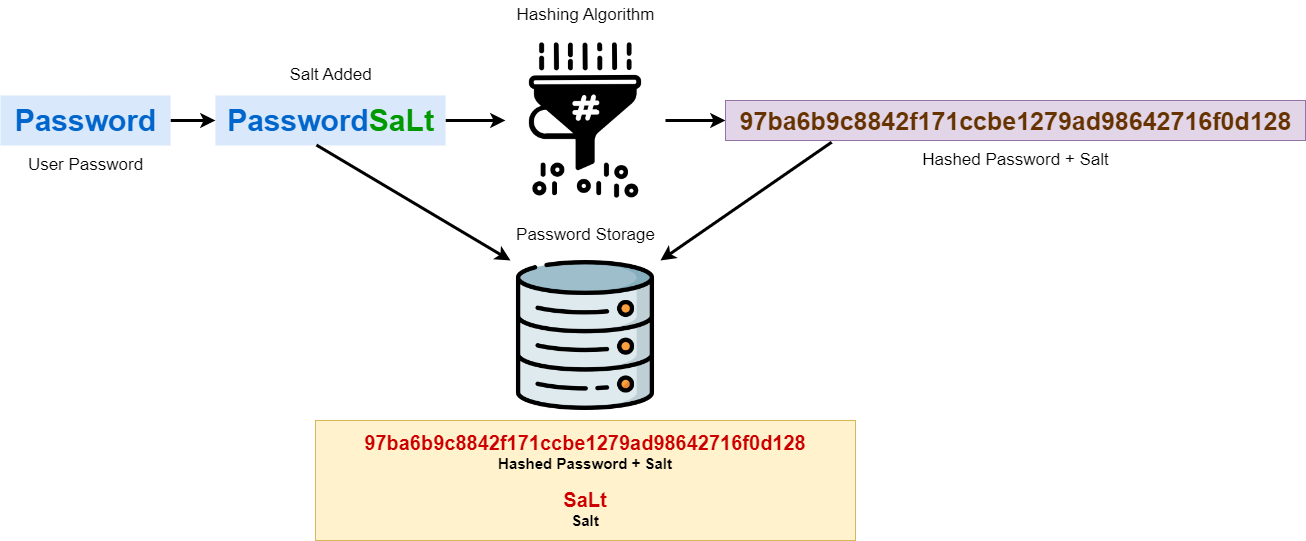

When a user creates or changes their password, the system generates a random saltIt combines it with the password (before, after, or in a specific format depending on the scheme) and applies a hash algorithm to that combination, such as SHA-256 o SHA-512The password is not stored in the database, but rather the hash of (password + salt), and in most schemes the salt itself is also stored along with the hash.

This technique renders many of the attack techniques based on precomputed hashes, like rainbow tables, and greatly complicates dictionary and brute-force attacks on a large scale. An attacker can no longer exploit the fact that multiple users share a password, because each one will have a different hash.

It's important to understand that salt is not a secret in itself: It is not a password or a private keyIts function is to introduce randomness and uniqueness into the hashing process. Security still depends on using strong passwords y suitable hash algorithms, preferably specifically designed for passwords (such as bcrypt, scrypt, Argon2), although many classic Linux systems use variants of SHA-256 or SHA-512.

How password salting works step by step

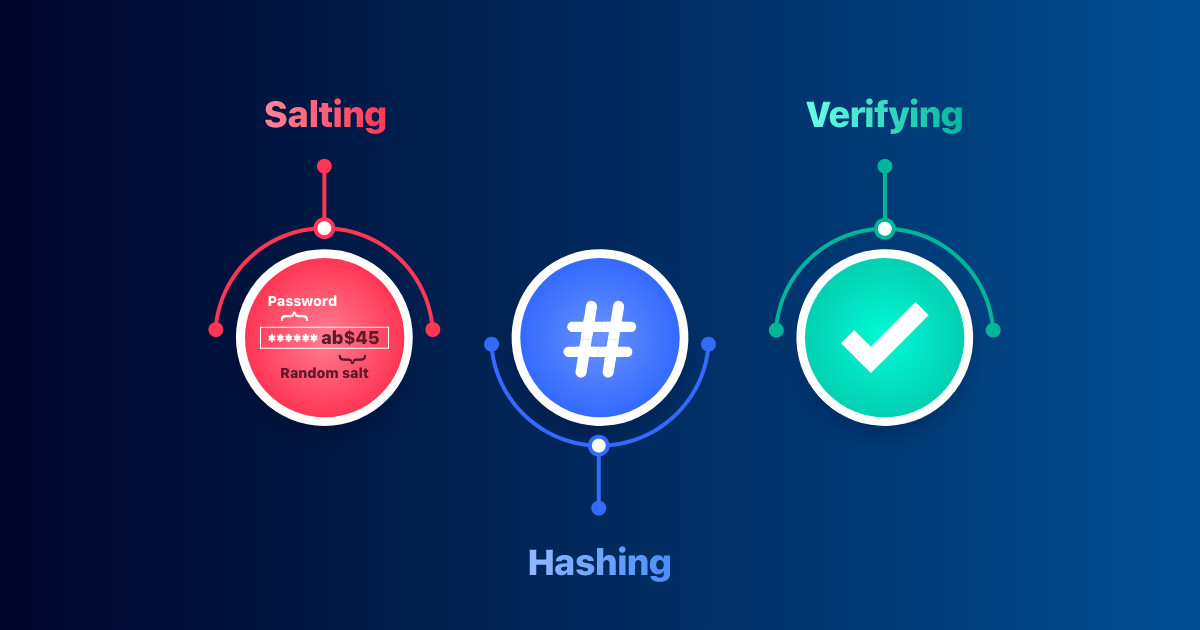

The salting process can be summarized in a series of fairly simple steps, but with a huge impact on security:

First, when a user registers or changes their password, the system generates a unique and random salt for that credential. That salt is usually of sufficient length (for example, 16 bytes or more) and is obtained from a cryptographically secure random number generator.

Next, the password chosen by the user is combined with that salt to form a intermediate chainThis combination can be as simple as concatenating salt + password, or it can have a more complex format defined by the hash scheme. The important thing is that each user ends up with a different combination.

Then, a one-way hash algorithmThe result is a seemingly random string, the hash, of fixed length, which will be stored in the database along with the salt. In modern systems, algorithms are being sought that produce long and complex exitsThis increases the search space and makes brute-force attacks more expensive.

Finally, when the user logs in, the system again retrieves the entered password. associated salt From the database, it repeats the exact same combining and hashing process and compares the result with the stored hash. If they match, it knows the password is correct without needing to know the plaintext.

This mechanism ensures that even if the database is leaked, the attacker will only see individual hashes with their own saltsInstead of a set of comparable hashes, stopping an attack isn't magic, but it does become significantly more computationally expensive.

Advantages of using salt in password hashes

The main reason for using salting is that strengthens the security of stored passwords against a wide variety of attacks. But it is worth detailing the specific benefits.

Firstly, salting provides resistance to dictionary attacksWithout salt, an attacker can prepare a huge list of common passwords and their hashes, and simply compare them to the stolen database. With a unique salt per user, those pre-calculated hashes become useless, because each password + salt combination generates a different value.

Secondly, the use of salt breaks down the effectiveness of the rainbow tablesThese are simply pre-calculated databases of hashes for popular passwords to speed up recovery. Again, since the result depends on the specific salt, these tables designed for unsalted hashes become useless or, at the very least, highly inefficient.

Another clear advantage is that it improves the privacy in case of leakEven if an intruder gains access to the user table with its hash and salt, they won't be able to quickly identify who has the same password as others or easily launch mass attacks. Each account requires individual attention, which is usually impractical on a large scale.

Furthermore, salting adds complexity to the brute force attacksInstead of being able to test a candidate password against all hashes at once, the attacker is forced to consider each user's salt, multiplying the total workload. If this is combined with a slow and parameterizable hashing algorithm (like bcrypt or Argon2), the attack cost increases even further.

Finally, salting is a technique that adapts well to technological evolution. Even as computer equipment improves and new attacks emerge, the combination of robust hash and unique salt It maintains a high and scalable level of difficulty: you can increase the length of the salt, strengthen the algorithm, increase the computational cost, etc.

How Linux implements password salting (/etc/shadow)

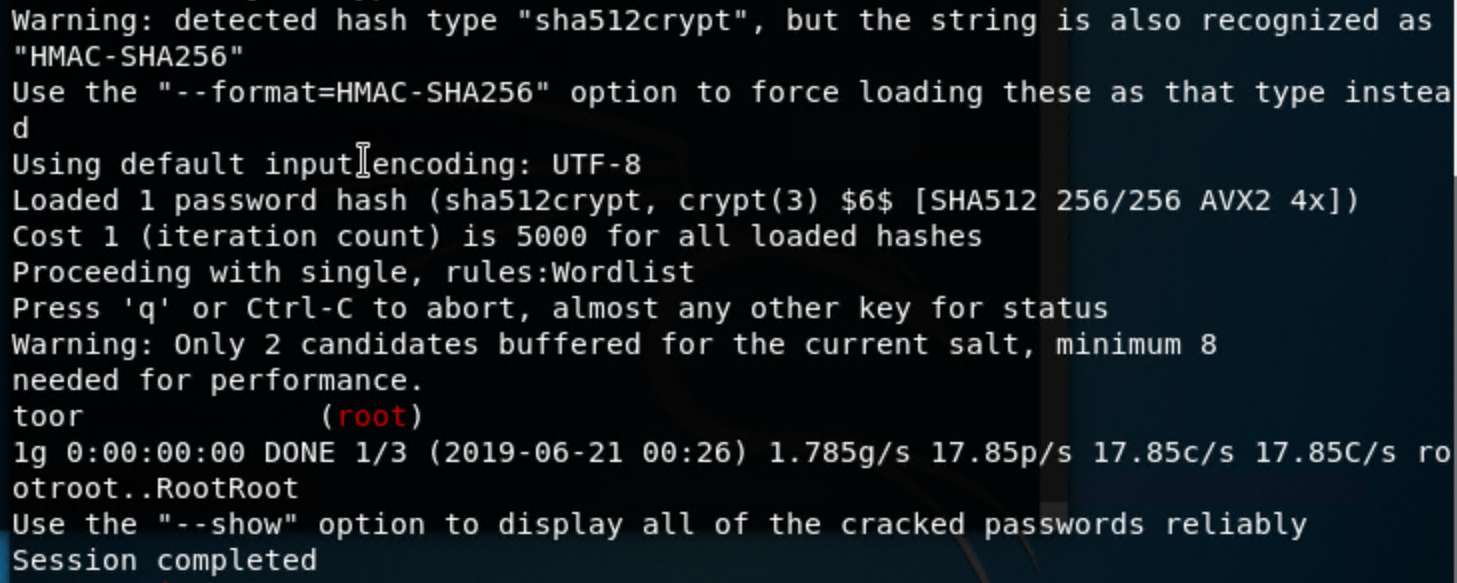

In Linux systems and other *NIX variants, user passwords are not stored in /etc/passwd, but in the file / Etc / shadowThis file, accessible only to the superuser, stores the password hashes along with additional information, and is where the use of salt and the hash algorithm is clearly seen.

The lines in /etc/shadow have a structure similar to:

user:$id$sal$hash:additional_fields…

The symbol $ Separate the different parts. The first part after the username indicates the type of algorithm used. For example, $ $ 1 usually represents MD5, $ $ 5 SHA-256 and $ $ 6 SHA-512, which is the most common algorithm in modern distributions because it offers greater security than older schemes based on DES or MD5.

After the algorithm identifier appears the shawland then the resulting hashAll of this is within the same field. When a password is validated, the system reads that identifier, the salt, applies the algorithm corresponding to the entered password, and compares the calculated hash with the stored one.

If you want to quickly inspect which users have encrypted passwords and what algorithm is being used, you can use a command like grep '\$' /etc/shadowIn this context, the dollar sign ($) is used to locate lines with hashes in modern format. The symbol must be escaped with a backslash because in regular expressions it signifies "end of line".

Accounts without a password or locked accounts usually display a value like this in that field. ! o * instead of a hash with dollars, indicating that it cannot be authenticated using a standard password. This structure makes one thing clear: Linux integrates salting into its format of storage passwords natively.

Difference between password hashing and salting

It is important to clearly distinguish between two concepts that are sometimes mixed up: hashing y saltingPassword hashing is the process by which a password is transformed into an unrecognizable value using a one-way algorithm. The server never needs to know the original password, only to verify that the user knows the correct password because it produces the same hash.

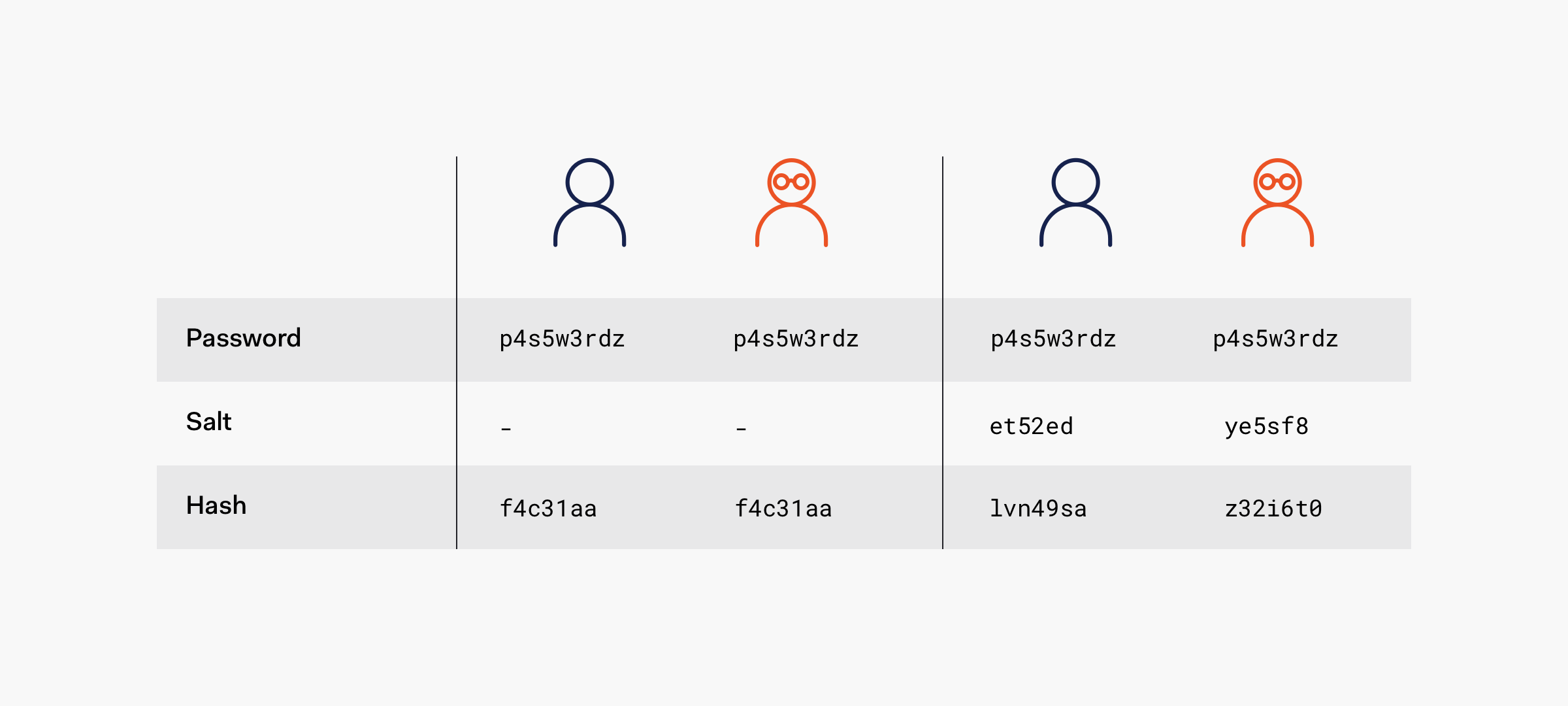

The problem is that if two passwords are identical, the Unsalted hash will also be identicalThis allows an attacker to compare and group users by password or use pre-calculated tables. Furthermore, if the hash algorithm is fast and designed for data integrity (such as simple SHA-256), it becomes more vulnerable to massive brute-force attacks.

Salting comes in precisely to solve that weakness: it's about add random data to the password before hashing it. The result is that even if two users choose “casa” as their password, the hashes in the database will be completely different, because one will have, for example, “casa+7Ko#” and the other “casa8p?M” as the pre-hash string.

Thus, hashing and salting do not compete, but rather complement each other. Hashing provides the unidirectionality property and ease of verification; the salt provides uniqueness and resilience against massive attacksA secure password storage implementation combines both techniques, ideally using an algorithm designed for this purpose, with configurable cost.

Using the salt in Linux with mkpasswd

In GNU/Linux environments and other systems UnixA very practical way to experiment with salting is the tool mkpasswdThis command is used to generate encrypted passwords securely, and is commonly integrated into user creation processes, administration scripts, etc.

The basic syntax of mkpasswd allows you to specify the password to be encrypted and a series of options such as the type of algorithm (for example, des, md5, sha-256, sha-512) using the option -mIn modern systems, the sensible thing to do is to opt for SHA-512 at a minimum, or by even more robust schemes if the distribution supports them.

The particularly interesting option in the context of salting is -SWhich enables add a salt to the password before encrypting it. If not specified manually, mkpasswd may generate a random salt in each executionso that even using the same login password, the resulting hash is different each time.

This can be easily verified: if you encrypt “password123” several times with mkpasswd, using SHA-512 and a random salt, you will obtain completely different hashes. However, if you pass the same salt value using -S, the hash will always be identical, because the password + salt combination does not change.

Thanks to this tool, it's very easy Prepare passwords encrypted with salt to add to configuration files, manage users manually, or test salting behavior without having to program anything.

Passionate writer about the world of bytes and technology in general. I love sharing my knowledge through writing, and that's what I'll do on this blog, show you all the most interesting things about gadgets, software, hardware, tech trends, and more. My goal is to help you navigate the digital world in a simple and entertaining way.